Growing from the STEM

How Women and Minorities at the University of Oregon Foster Diversity in STEM.

During a youth outreach event, Lisa Eytel, a fourth-year Ph.D. student studying organic chemistry at the University of Oregon, asked students to draw a scientist. Most drew males.

Similarly, this result aligns with a research study published in 1983 by social scientist David Chambers. Between 1966-1977 almost 5,000 kids ages five to eleven years old were asked to draw a scientist.

Out of those drawings, only 28 female scientists were drawn, all by girls.

There may be a reason for this. Women are still underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields. Engineering, for example, shows the greatest disparity with a female workforce of approximately 15 percent as of 2015, according to the National Science Foundation.

Along with underrepresentation, many women also experience exclusion.

While visiting potential graduate schools, Eytel toured a campus she was very interested in that had a program similar to University of Oregon’s. Walking into an organic chemistry lab of approximately 20 students she asked a graduate student why there weren’t more women in his group. The student replied that women don’t do organic chemistry. Eytel decided not to attend that school.

“A program that cultivates a culture like that is a red flag for any gender minority or ethno-racial minority, or sexual orientation minority, whatever it may be, it should be a red flag for everybody,” she said.

The scientists

Please click an image then roll your mouse over the image to learn about each person.

“As a woman in science, I see quite a bit of discrepancy in treatment towards gender-minorities.”

Now at the University of Oregon, Eytel serves as the outreach co-chair for the Women in Graduate Science group, a student organization that strives for gender equality by focusing on professional development of women in all disciplines of science, according to it’s mission statement. She also co-founded the newly formed, LGBT in STEM.

“I got involved because as a woman in science, I see quite a bit of discrepancy in treatment towards gender-minorities,” she said.

SOURCE: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Scientists and Engineers Statistical Data System (SESTAT) (1993–2010), http://sestat.nsf.gov.

According to statistics from the Economics and Statistics Administration, in 2015 women made up 47 of the U.S. workforce but only 24 percent of STEM jobs. Similarly, women with STEM degrees are more likely to work in healthcare or education as opposed to a STEM occupation.

To foster an inclusive environment in STEM fields, several student organizations have emerged on campus. Providing mentorship, youth outreach and a community, these groups support women and minorities to foster diversity in STEM.

These groups include but are not limited to: Women in Physics (WiP), LGBT in STEM, Association for Women in Mathematics (AWM), Communities for Minorities in STEM (CMis) and the largest, Women in Graduate Sciences (WGS), consisting of over 150 members.

Pursing a STEM degree in graduate school can be isolating as oftentimes you only interact with those in your labs. With isolation, comes feelings of not belonging or imposter syndrome. These feelings are not limited to gender-based minorities, but also sexual orientation minorities and ethno-racial minorities as well.

Jacyln Kellon, fourth-year chemistry Ph.D. student said on deciding to come to graduate school, “I knew that I was going to be one of very few women of color, specifically women of color in a doctoral program in chemistry. I knew that would be hard, but I didn’t realize that moving to Eugene would be so challenging.”

Struggling with a sense of belonging, she questioned if she wanted to continue with the program.

During a presentation on the social psychology of women's underrepresentation in STEM, Dr. Sara Hodges said, "This is the most women in one room talking about science I think I have ever seen." The presentation was part of an Undergraduate Women in Physics Conference held at the University of Oregon in January 2018.

These internal challenges often come down to representation, or lack thereof. Dr. Jenefer Husman, an educational psychologist who studies how students imagine their futures, said students can envision their future selves by seeing someone who represents them as a role model. Her research suggests a correlation between the way you imagine yourself and your academic achievements, saying you have to look beyond the obstacle in front of you because if not, you’ll stumble on it.

But, without having a role model, or someone you feel represents you, finding your academic identity can be challenging.

“I felt this really innate sense of otherness that I hadn’t felt anywhere else,” Kellon said. So, in 2016 she started CMiS thinking she couldn’t be the only one to feel that way. It now has approximately 30 members and draws upwards of 60 attendees to events.

“I don’t want people to think the reason I’m here is because I’m meant to fill a quota.”

Similarly, having a sense of community and belonging is also important. When physics Ph.D. candidates Kara Zappitelli, Alice Greenberg and Amanda Steinhebel attended a Pacific Northwest retreat for women in science with over 100 women, they found they were three of only five physicists in attendance. Wanting a community where women and women-identifying physics students could connect, they started the WiP group.

Physics has one of the most disproportionate gender imbalances with women accounting for only 20 percent of Ph.D. recipients according to the American Physical Society.

Zappitelli said at the time the group was started, the physics department had about 12 percent females and female-identifying students.

“Our labs at the University of Oregon aren’t that big, so that means in your lab you’re most likely the only woman,” she said. Without a platform to meet other women, you weren’t likely to interact with other women in the deparment.

Zappitelli said, “We all have shared experiences. It’s hard to be underrepresented.”

For ethno-racial minorities, there is also the added internal pressure of representing your racial community.

“I don’t want people to think that the only reason I’m here is because I’m meant to fill a quota,” Kellon said, adding, “I don’t want to look incompetent or stupid and reflect poorly on my race.”

After starting CMiS, she began to feel more at home on campus after making friends outside of her department and forming relationships that go beyond just talking about the science.

“Science is all factual, but what we choose to experiment with is heavily influenced by our life and life views.”

the next generation

These student organizations aren’t just a source of support and camaraderie, the groups also offer mentorship and outreach programs to foster the next generation of women and minorities in STEM.

Astronaut Wendy Lawrence answers questions from the Girls' Science Adventure workshop participants in the Eugene Science Center planetarium.

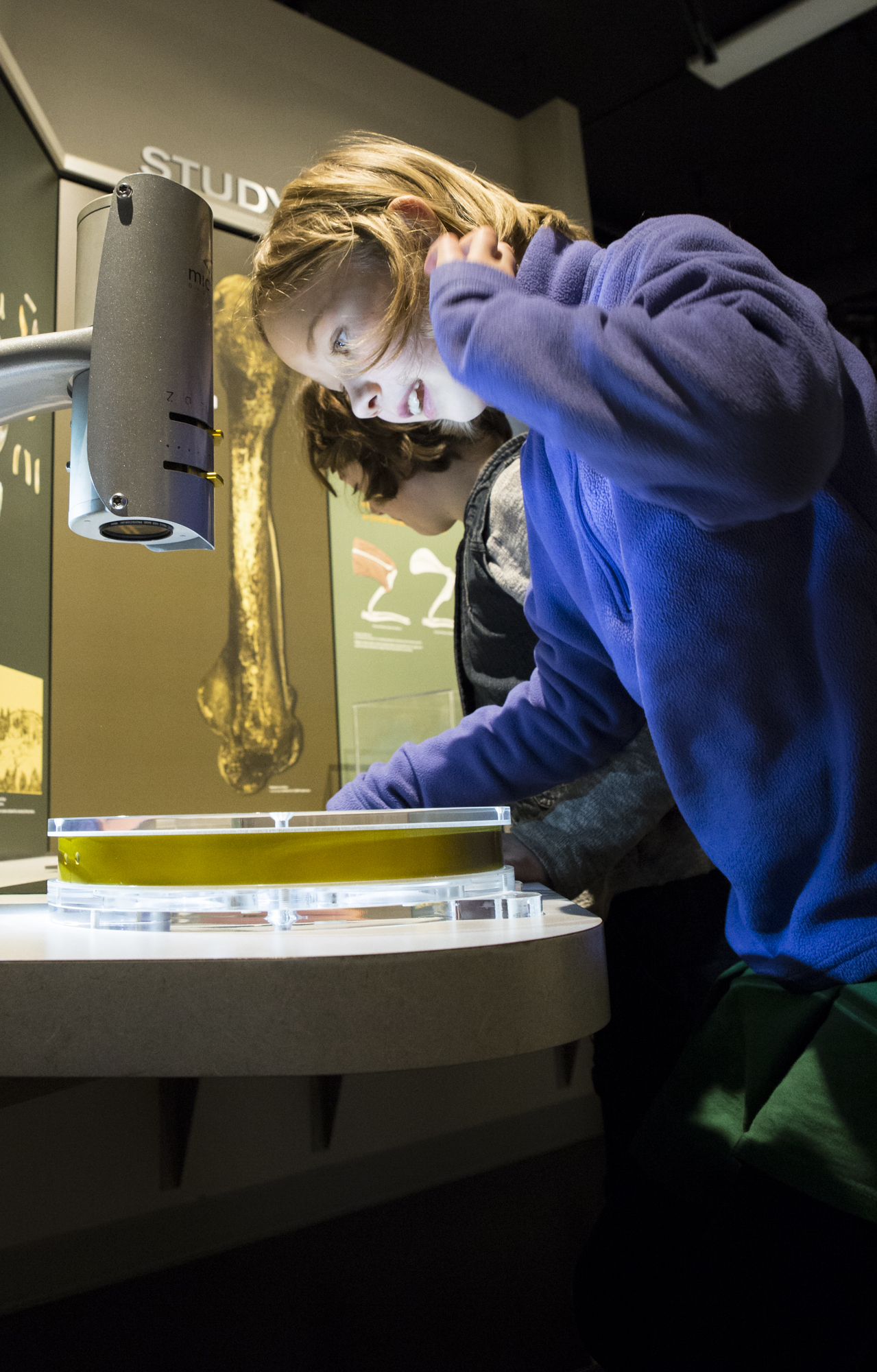

This past winter, WGS and Eugene Science Center teamed up to offer a six-week Girls’ Science Adventure series on Saturday mornings. Led by Eytel and fellow outreach co-chair, Dana Reuter, workshops were taught in forensic science, geology, astronomy and more with the final event being a meet-and-greet with astronaut Wendy Lawrence.

Reuter said, “Young girls in a classroom setting don’t talk as much, even among their peers they talk about how they don’t like math or science or that girls can’t do science, so encouraging them, specifically seeing women role models is really important.”

The importance of representative role models is evident in a study conducted by Microsoft. In surveying girls in grades 5th-12th, of those who know a female in STEM, 61 percent report feeling powerful while doing STEM activities as opposed to 44 percent for those who do not know a female in STEM.

Through outreach efforts, the WGS hopes to change the culture of science by showing kids a diverse array of what scientists look like. Diverse viewpoints lead to diverse ideas and solutions.

“Science is all factual, but what we choose to experiment with is heavily influenced by our life and our life views,” Eytel said. In having a more diverse science community, you allow for diversity of thought and get different ideas and perspectives on things.

“Science already heavily impacts society in every way shape and form, everything we do every day is thanks to advances in sciences and technology,” Eytel said, “But I think we might make a number of steps forward by having more and more women and other minorities in the field.”

With community support, outreach and mentoring efforts made by these groups, the hope is that one day kids will draw a different kind of scientist, one that looks just like them.

Astronaut Wendy Lawrence, center top row, stands with the Girls' Science Adventure workshop participants. Lawrence was invited by UO Women in Graduate Science to encourage young girls to stay excited about science.